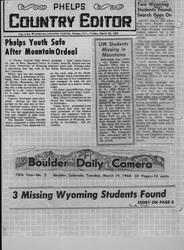

My first real backpacking trip in 1968 was more than just a little adventurous. It turned out to be a formative experience. Al Hendricks (from Valhalla, New York), Dennis Alf (from Berlin, Wisconsin) and I planned a 30-mile overnight trip over Rollins Pass in Colorado. Now, keep in mind you have three eighteen-year-olds, two from New York State and one from Wisconsin, planning to hike over 11,671 ft Rollins Pass during the Ides of March. In some parts of the world March 15th is considered spring but in the Rocky Mountains you are still enjoying the snows of winter. In those days winter camping was reserved for relatives of explorers Roald Amundsen, Sir Robert Scott, Admiral Perry, Ernest Shackleton and a few weirdos. Cross-country skiing had yet to become popular in the U.S., and snowshoeing was an activity left for hunters and trappers. We had one of Dick Kelty’s early backpacks between the three of us, no snowshoes and were wearing blue jeans. No, come to think of it, I was wearing beige jeans. (Pile hadn’t been invented and although we wore some wool, we weren't familiar with its virtues.) The sum total of our experience was my summer family motorboat and car-camping experiences and Al’s weekend hikes on the Appalachian Trail. We took off from Laramie, Wyoming for Tolland, Colorado and the East Portal of the famous seven-mile-long Moffat railroad tunnel. We planned to hike the gently winding abandoned railroad bed over the pass to Winter Park and then take the train back through the tunnel to our red VW Beetle on the east side of the mountains.

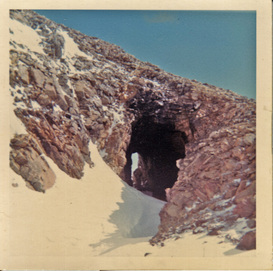

We started out on that beautiful March day with the sun shining brightly on the magnificant, snow-covered peaks. We were confident that we would have no trouble hiking the sixteen miles through the three-inch-deep snow up to the “Needle’s Eye” tunnel where we hoped to set up Al’s two-person, two-foot-high nylon pup tent.

We hiked about a half-hour, came around to the north side of the ridge and, to our surprise, the snow was crotch level. Our youthful enthusiasm carried us through a 100-yard stretch of this deep snow until once again we found the going easy through ankle-deep snow. We kept up a good pace all day and finally, just before dark, could look up and see the small 150-foot-long tunnel along the side of the mountain a quarter of a mile above us. We scrambled a direct route up the talus slope to what is called the Needle Eye Tunnel, saving about a mile of hiking distance but breaking an, unknown to us, cardinal rule of hiking, “Never cut across switchbacks.” As darkness rapidly descended, we set up the two-man tent, threw in our sleeping bags, grabbed a bite to eat and crawled in. Now imagine three husky college boys squeezing into a tent designed for two with barely enough room to sit up. Al had a high-tech down sleeping bag while Dennis and I had kapok-filled bags with pheasant-hunting scenes decorating the cotton liners. We tossed and turned on top of each other while the wind howled and the snow blew outside the protecting walls of the tunnel. Hearing the wind and blowing snow, we wondered what awaited us in the morning. We awoke early to temperatures in the single digits and eagerly crawled from our frosty tomb to a gorgeous sunrise surrounded by rocky peaks. The panoramic view of what is today the Indian Peaks Wilderness kept our little Instamatic cameras humming and gave us confidence that we would have no problem finishing our trip.

We were confident that by morning we would hear the hum of a snowmobile, our rescuers would pull up to the outhouse, and we would climb aboard and zoom out of the wilderness. The reason for this false hope was that the other smart thing we did was tell our friends and even our dormitory’s resident advisor where we were going and when we should return. We had said that if we weren’t back by Sunday night that something was wrong. Little did we know that back at the dormitory our friends were saying, “Oh, their car probably broke down. They’ll be back tomorrow.” They found every reason to rationalize our absence and didn’t report us missing until Tuesday morning.

Meanwhile, back in the outhouse we had spent a restless Sunday night. Monday was spent anticipating rescue and dealing with the 11,000-foot altitude, which was affecting all of us somewhat but affecting our most experienced hiker, Al, the most. The effects of altitude, headaches and a little nausea kept us from eating as much as we should. We were out of water, so occasionally we dipped our cups into the snow for semi-liquid refreshment. Every time we heard a plane fly over, one of us would climb out to check if it was a search plane. The only planes we saw were commercial jets flying at over 30,000 feet.

In the afternoon, partly out of boredom and partly to generate some warmth, we decided to expand our living quarters. Dennis, who was a member of the university’s wrestling team, punched his fist through the plywood partition separating the women’s section from the men’s and we tore down half the wall. We decided to build a fire in the women’s half of our domain and, after climbing through the deep snow to break branches off the coniferous trees and much coaxing of the toilet paper and small twigs, we finally got the green wood to provide a smoky excuse for a fire. Dennis, who took the lead in this endeavor, had worked up an appetite, so he tossed on a can of baked beans before returning to the warmth of our sleeping bags. We lay in our bags discussing our situation when all of a sudden we heard a loud bang! Not being a connoisseur of outdoor cooking, Dennis didn’t know that one has to put a hole in the can if you are to cook baked beans in the can. The can exploded, sending baked beans all over the walls of the women’s side of the outhouse. That provided one of a number of good chuckles.

Al and I were confident we would not end our lives in an outhouse, but Dennis was not so sure. At one point while tending the fire, he took a burnt stick and wrote his girlfriend Mary’s name on the wall as if he might never see her again. He maintained his sense of humor, however, when on Tuesday night, as we lay huddled in our zipped-together sleeping bags braced against the cold, he said, “You know, Mary will probably never forgive me. I told her I’d never be in anyone else’s arms.”

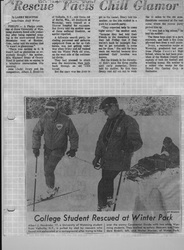

On Monday evening, we decided that if no one had arrived to rescue us Tuesday morning we would leave any extra food with Al, who was still suffering from the altitude, and Dennis and I would hike out to get help. Awaking early Tuesday with no rescuers in sight, Dennis and I headed out through the deep snow with only the clothes on our back. We plodded through the deep snow for about a mile when, lo and behold, the snow was firm enough to walk on. A snowcat had been up the trail within the last week and had packed down the snow well enough to walk on. We scrambled down the road quickly, once taking a waist-deep short cut between switchbacks. (The ranger told us later we saved over a mile of walking this way.) At this point Dennis felt he had worn a hole through his sock and it was driving him crazy, so we stopped to adjust his socks. If we had extras, which I doubt, we had left them with Al. He took off his boot and, lo and behold, there was no hole in the sock. We didn’t know what to make of it, but he put his boots back on and we continued down the mountain.

We made good time and arrived in the village of Winter Park around 10:00 a.m. We went to the first public building we saw, which happened to be the Post Office. We walked in and asked the friendly lady at the counter if she had heard of any boys being lost in the mountains. She responded no but offered to call the ranger and check with him. Evidently search parties were just getting organized. While waiting for the ranger to come and pick us up, we asked the postal clerk if she had any water. She was sorry that she couldn’t help us with water but she did have a couple of candy bars. Have you ever tried to eat a Butterfinger candy bar without having had anything to drink for 24 hours? We had given little thought to how dehydrated we were; we felt fine except for Dennis’ sock that didn’t have a hole in it.

The ranger pulled up in his green U.S. Forest Service truck and got out to greet us. In typical Rocky Mountain understatement, he said, “It must be spring is coming, ’cause the fools are gettin’ out into the mountains.” Well, that perked up our self-esteem, and we hopped into the truck to travel the short distance to the Forest Service headquarters. The little building was humming with folks preparing to head out and look for us. Evidently, they were planning a variety of search strategies. They had folks approaching the pass from the north and the south, and folks with ice axes, crampons and ropes were ready to scale cliffs. They seemed to have every route covered except the most obvious one, following up the Rollins Pass road we were hiking on.

A number of rescue folk asked how we were and, of course, we said fine except for Dennis’ sock that didn’t have a hole in it. They asked to take a look. Dennis removed his boot and sock and his big toe was whitish gray and cold and stiff to the touch. They had just recently completed a seminar on frostbite and they thought that might be Dennis’ problem, and sure enough, it was. It was comical to watch four adults surrounding Dennis’ toe, pointing, poking, prodding and saying, “Yup, just like the pictures in the seminar. This here is frostbite!” They whisked Dennis off to Colorado General Hospital in Denver, where he spent the night and was released, no worse for wear after being treated for superficial frostbite of his big toe. Meanwhile, a small team of rescuers took a snowcat up the road to rescue Al. Al was tired but otherwise in good shape.

Our college buddies from Laramie came down and picked up Al and me, and we headed back to campus. Our misadventure made pretty big headlines across the country, much to our chagrin, and we weren’t surprised when a week later we received a bill from the Forest Service for $68.23 to repair the damage done to the outhouse.

We were lucky. We were poorly dressed, lacked the proper equipment (especially snowshoes), and did not have enough food and water, but we were blessed with relatively mild weather. I think the only reason we didn’t get hypothermia (as Paul Petzoldt frequently said) was because the word hadn’t been invented yet. On the other hand, considering how little experience we had, we did do one thing right. We did let people know where we were going and when we expected to return.

In a letter to us after the incident, the Ranger hit the nail on the head when he said, “I am sure you realize the severe potential consequences had the weather been stormy…it is rather foolish to attempt crossing Rollins Pass during the winter, being poorly prepared…This high country is very hostile during the winter and should not be treated lightly. The next time you plan a trip of this nature, it would be wise to check with someone who knows the country so you will be better prepared to encounter the difficulties that you may encounter. All too many times weekend mountain trips have turned into disaster for college students. Most of these past cases…can be related back to poor preparation, lack of equipment, inexperience and poor judgment in leadership of the party.” (See the complete letter and the bill from the USFS below)

When three-and-a-half years later, I climbed Denali, the highest mountain in North America at 20,320 feet, many of my hometown friends thought I was completely insane. Just the opposite was true, because at that time I knew quite a bit more about what I was doing. After my experience on Rollins Pass, I got the outdoor bug and decided I wanted to do it right. I had the opportunity to hear Paul Petzoldt talk on the University of Wyoming campus the following year about this school he had started called the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS). The school curriculum sounded exactly like what I wanted to do. A year and a half later, I took the NOLS 35-day wilderness course in the Wind River Range of Wyoming. The following summer I was part of NOLS’ first attempt to climb Denali, and a couple of years later I successfully completed the NOLS Instructor course.

(click on the photos below to learn a little about each photo)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed